Key Findings

- Most states taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities.

business personal property (machinery, equipment, fixtures, electronics, etc.), but of the 36 states that tax it, 10 states and the District of Columbia provide an exemption for small businesses with little tangible personal property. - The vast majority of personal property taxA property tax is primarily levied on immovable property like land and buildings, as well as on tangible personal property that is movable, like vehicles and equipment. Property taxes are the single largest source of state and local revenue in the U.S. and help fund schools, roads, police, and other services.

revenue comes from a very small number of large businesses and utilities. - Complying with personal property taxes is onerous, as it requires documenting all assets—all the way down to cleaning supplies for the office kitchen—along with their acquisition price, acquisition date, and depreciationDepreciation is a measurement of the “useful life” of a business asset, such as machinery or a factory, to determine the multiyear period over which the cost of that asset can be deducted from taxable income. Instead of allowing businesses to deduct the cost of investments immediately (i.e., full expensing), depreciation requires deductions to be taken over time, reducing their value and discouraging investment.

. - Creating a threshold under which there is no liability or reporting requirement eliminates these compliance burdens for the overwhelming majority of businesses at a trivial cost to the government.

Introduction

All policy choices involve trade-offs—but occasionally, the ratio of costs and benefits is shockingly lopsided. Adopting a de minimis exemption for tangible personal property (TPP) taxes is just such a policy: one which massively reduces compliance and administrative burdens at trivial cost. Taxes on TPP (business machinery, equipment, fixtures, and supplies) are a small but still meaningful part of the property tax baseThe tax base is the total amount of income, property, assets, consumption, transactions, or other economic activity subject to taxation by a tax authority. A narrow tax base is non-neutral and inefficient. A broad tax base reduces tax administration costs and allows more revenue to be raised at lower rates.

in most states. However, the vast majority of revenue comes from extremely few businesses, while small and medium-sized businesses absorb substantial compliance costs—and local governments face substantial administrative burdens—to remit a few dollars in taxes.

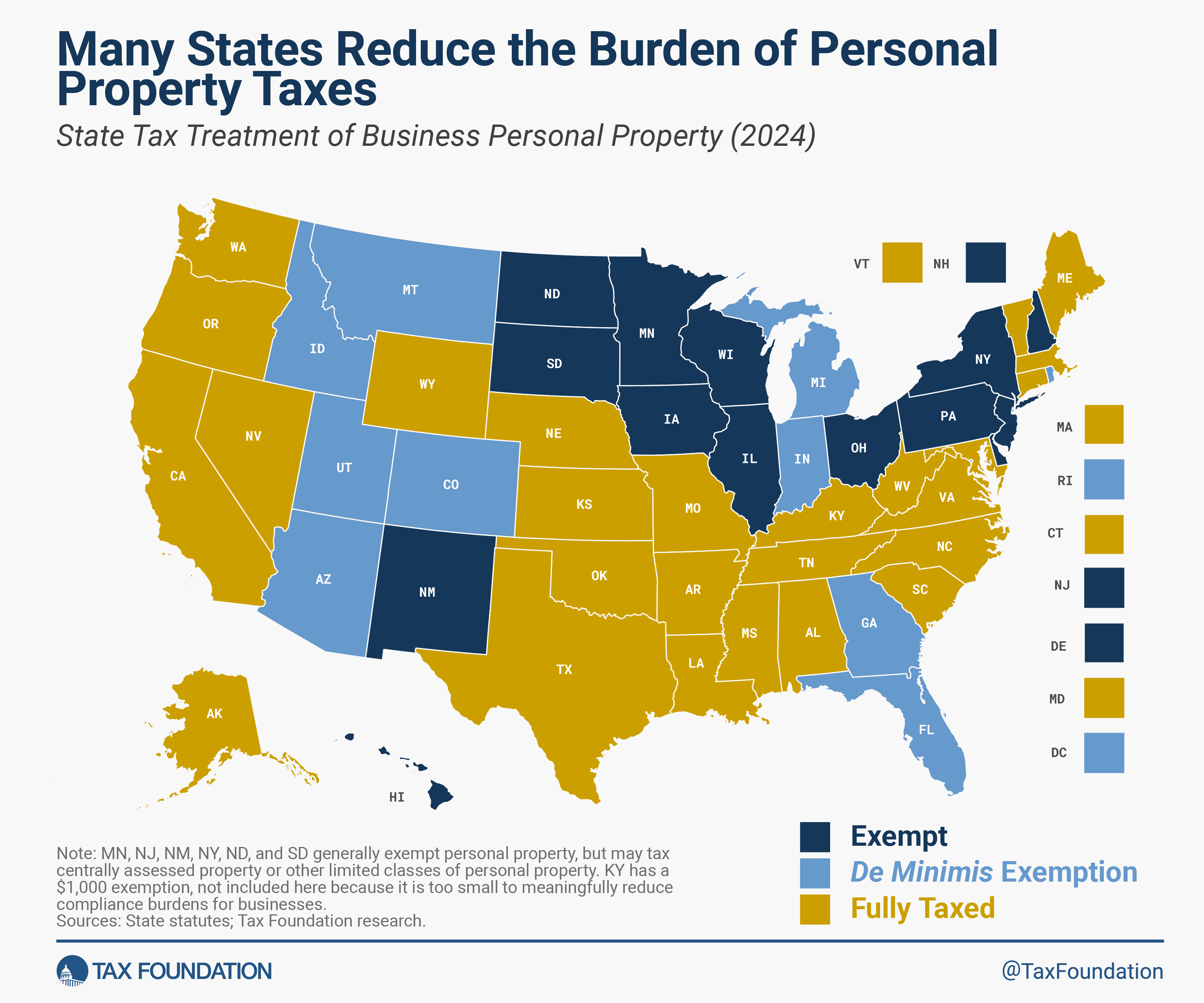

Adopting an exemption for modest amounts of TPP costs governments extremely little, with substantial benefits to taxpayers and tax administrators. Unsurprisingly, such thresholds are catching on in red and blue states alike. Twenty-four states and the District of Columbia either broadly exempt TPP from taxation (14 states) or provide an exemption for small businesses with little tangible property (10 states and the District of Columbia).[1]

Idaho recently exempted 90 percent of all businesses at a cost of about 1.1 percent of property tax collections. Indiana exempted at least 70 percent of businesses for less than 0.5 percent of property tax collections. The District of Columbia exempted 97 percent of businesses from TPP taxes by forgoing less than 1 percent of its property tax revenue.[2] And Colorado recently raised its threshold from $7,900 to $50,000—exempting the majority of businesses—at a cost of less than one-sixth of one percent (0.15 percent) of property tax revenue.

In an ideal world, governments would not tax tangible personal property at all, as the tax lacks the justifications that undergird the taxation of real property (land and structures), and, unlike a tax on real estate, taxes on personal property are a direct levy on capital investment and impose significant compliance burdens. Some states are in a position to eliminate TPP taxes altogether, particularly if they generate very little revenue—as is often the case, as the share of revenue from personal property taxes has declined dramatically over the decades. Others may find it more difficult to repeal the tax, despite its economic shortcomings. But any state could adopt a de minimis exemption at very little cost, while dramatically reducing compliance burdens for the vast majority of the state’s businesses.

Personal Property Tax Definitions and Compliance Burdens

Although they once applied to the property of individuals and businesses alike, tangible personal property taxes now fall almost exclusively on the moveable property of businesses, whether corporations, pass-through entities, or sole proprietorships. One major exception, discussed later, is automobiles, which are sometimes taxed—for businesses and individuals alike—as tangible personal property.

Just about anything possessed by a business other than real estate, intangibles, and intellectual property constitutes personal property. Maryland’s definition is typical: “The term ‘Personal Property’ specifically includes property owned by the business, leased by the business or used by business, even if that property is owned by another business or individual. ‘Personal property’ includes computers, phones, cell phones, furniture, draperies, inventory, equipment, tools, machines, books, artwork, supplies and fixtures.”[3]

Personal property is valued based on the initial acquisition price as well as the age of the asset, as such property is “depreciated” according to straight-line schedules published by each state with a TPP tax. Depreciation is a measure of the “useful life” of a business asset, with the taxable value of the asset declining over time. For instance, an asset with a five-year life would be taxed at 100 percent of acquisition value initially, then 80 percent of acquisition value the next year, 60 percent the year after, and so on, until in the sixth year, it has no taxable value (though it may still need to be reported). Often, however, an asset is not permitted to depreciate below a particular threshold even after the end of its “useful life” according to the depreciation schedule.

Complying with tangible personal property taxes is needlessly complex. Consider the District of Columbia, which spares small businesses from tax liability but still requires all businesses to file accurate returns, even if their property is well under D.C.’s fairly generous $225,000 exemption. The District has seven categories of tangible property, each with a different depreciation schedule ranging from 2- to 15-year lives or no depreciation (100 percent of cost) at all. Identifying the correct depreciation schedule can be maddening: electronic manufacturing equipment, for instance, has a 5-year life, while fabricated metal products equipment has an 8-year life, paper products equipment has a 10-year life, plating equipment has a 15-year life, and certain qualified technological equipment gets special treatment. Since the 94 categories of tangible property provided are far from all-encompassing, the instructions booklet helpfully offers that “[d]epreciation rates for tangible personal property not listed in the Depreciation Guidelines in this booklet may be obtained by calling [the tax department’s number].”

Each business location with personal property must have its own schedule or set of schedules, and there are different schedules or sub-schedules for (1) reference materials; (2) furniture, fixtures, and machinery and equipment; (3) motor vehicles not registered in D.C.; (4) miscellaneous tangible personal property; and even (5) supplies. For tax purposes, businesses must report office supplies like stationary and envelopes, or the office kitchen’s cleaning supplies and cutlery. Outdoor Christmas decorations are depreciated over five years, as are the business’s carpets, while paper products are reported at full cost, and desks, chairs, and cabinets depreciate at 10 percent per year.

In D.C., assets cannot be depreciated in excess of 75 percent of their original cost, so even after the depreciable life of the asset, they continue to be assessed at 25 percent of acquisition cost—unless they constitute qualified technological equipment, which drops to 10 percent of original cost. Businesses must report the acquisition price and date, current (depreciated) value, and the disposition of any tangible personal property sold, donated, discarded, or traded. Leased property must also be accounted for, through a separate schedule.[4]

In Florida, which provides a $25,000 exemption, the Monroe County appraiser’s office answers several common questions on its website, which serve to illustrate how burdensome tax compliance is:

Who must file a personal property return?

Anyone in possession of assets on January 1 who has either a proprietorship, partnership, corporation or is a self-employed agent or contractor, must file each year. Property owners who lease, lend or rent property must also file a return. […]

What If I have no assets to report?

Even if you feel you have nothing to report, complete the return form, attach an explanation about why nothing was reported, and file it with the property appraiser’s office. Almost all businesses and rental units have some assets to report, even if it is only supplies, rented equipment, or household goods. […]

What if I have old equipment that has been fully depreciated and written off the books?

Whether fully depreciated in your accounting records or not, all property still in use or in your possession should be reported.

Do I have to report assets that I lease, loan, rent, borrow or are provided as part of the rent?

Yes. There is an area on the return specifically for those assets. Even though the assets are assessed to the owner, they must be listed for informational purposes.

Is there a minimum value that I do not have to report?

No. There is no minimum value. A personal property tax return must be filed on all assets by April 1. However, if the resulting property taxes amount to less than $5.00, you will not receive a tax bill.[5]

Worse, forms may vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction. Twenty-seven states and the District of Columbia furnish a uniform tangible personal property declaration form that can be used across the state, though the form must still be filed with each jurisdiction separately. In other states with TPP taxes, firms must use locality-specific declaration forms and processes to calculate and remit their TPP tax liability.[6]

At some level, almost everyone recognizes that this is ridiculous. Businesses have to report on the acquisition date and costs of their carpets, drapes, computers, and paper products, and even have to provide a cost figure that includes things like the dish soap in the office kitchen. (Unsurprisingly, compliance levels are notoriously scattershot, and tax agencies lack the resources or motivation to auditA tax audit is when the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) conducts a formal investigation of financial information to verify an individual or corporation has accurately reported and paid their taxes. Selection can be at random, or due to unusual deductions or income reported on a tax return.

or enforce the tax consistently.) This is radically different than the real property tax, where an assessor establishes the taxable value of a parcel, and the taxpayer simply remits the amount indicated on their tax bill.

Existing TPP Tax Regimes

In 14 states, personal property is either fully exempted or only applies to very limited categories of (generally) centrally assessed property, like utility or railroad property. Another 10 states and the District of Columbia have adopted exemptions for businesses with only modest taxable assets. In most but not all cases, businesses under these exemption thresholds have no obligation to file tax returns. Requiring a business to go through the entire process of valuing and reporting personal property even when it is self-evidently well below the remittance threshold eliminates the compliance savings of the exemption, which is arguably more significant than the actual tax savings.

The share of property tax revenue generated from personal property varies widely from state to state, dependent on factors such as the state industry mix, differential assessment ratios on personal property or on business and commercial property more broadly, and the comparative value of residential property. Among TPP-taxing states for which data are available, personal property taxes are responsible for 0.9 to 29.4 percent of property tax collections, with a median share of 6.4 percent. Nationally, we estimate that personal property taxes are responsible for 5.4 percent of property tax collections, or about 4.6 percent if one excludes car taxes which are included in some states’ personal property tax regimes.[7] Naturally, full repeal of TPP taxes is more easily accomplished in states with limited local reliance on the tax, though even states with high reliance can find de minimis exemptions quite cost-effective.

Implications of Taxing Personal Property

Real property taxes—on land and buildings—are often justified as a benefits tax, where property is taxed roughly commensurately with the value of services received. Land is made more valuable by good roads, school systems, law enforcement, and emergency services. Real property is also immobile, such that taxes on real property introduce relatively few economic distortions.[8]

Personal property, by contrast, is more mobile: it can be located elsewhere, or sold if unproductive or unprofitable. And whereas there is a fixed supply of land (even though different uses can increase or decrease housing, production, etc.), levels as well as locations of capital investment may be influenced by personal property taxes. Local tax administrators can exercise only limited oversight over personal property, moreover: whereas mapping, zoning, and building permit systems provide local officials with a reasonable view of real property, governments lack similar insights into personal property, and rely instead on self-assessment, a characteristic which led one observer, more than 80 years ago, to term the TPP tax a “tax on honesty.”[9]

Tangible personal property taxes fall on business assets used to generate a return, which is reduced by the tax. On the margin, this decreases business investment, as it increases the investment return required for an asset to be profitable. The tax is levied without regard to a company’s profitability, and it is most burdensome on assets that generate low rates of return—those that tend to be most sensitive to taxation. Studies show that eliminating TPP taxes increases capital investment, with resultant improvements in labor productivity and employee wages.[10]

If businesses operate in a competitive multistate environment, they have limited ability to shift TPP tax costs to consumers in the form of higher prices. Instead, the tax’s costs will manifest in reduced investment, lower investment returns, and lower wages. In the cases of purely local competition (where, for practical or legal reasons, out-of-state firms cannot compete), more of the cost of the tax is likely to be borne by consumers.[11]

Only repeal of TPP taxes can yield these effects, not higher exemption thresholds, since the vast majority of taxable capital investment is above these thresholds. Adopting a de minimis exemption does very little to ameliorate the economic distortions imposed by the levy itself. But it goes a long way toward reducing another kind of distortion, in the form of high compliance costs for minimal revenue generation.

Case Studies in TPP De Minimis Exemptions

Eleven states have adopted TPP de minimis exemptions, with Rhode Island joining the list most recently, in 2023, while several other states simultaneously raised their exemption thresholds. Four brief case studies, from Colorado, Idaho, Indiana, and Utah, illustrate that meaningful exemptions are in reach for states across the country.

Colorado

In Colorado, personal property accounts for 11.7 percent of property tax-assessed value, significantly higher than the national average. Nevertheless, a recent expansion of the exemption from $7,900 to $50,000 only cost $19 million, roughly 1.2 percent of personal property tax collections and 0.15 percent of all property tax collections.[12] The state reimburses localities for the loss of revenue. This is partly due to the nature of Colorado’s personal property, the majority of which comes from oil and gas, railroads, mines, and other large industrial businesses, many of which are state-assessed. Although no recent breakdowns are available, in 2013, only 41 percent of tangible personal property value came from commercial, industrial, or agricultural businesses,[13] and it is these businesses that benefit from the relief.

Idaho

In Idaho, where personal property accounts for 7.01 percent of assessed value,[14] lawmakers recently expanded the exemption from $100,000 to $250,000 at an estimated statewide cost of $8.1 million.[15] The exemption of the first $100,000, beginning in 2015, was projected to eliminate filing obligations for 90 percent of all businesses at a cost of $20 million.[16]

Idaho’s property tax effective rates were more than twice as high in 2015 as they are now (rates have declined as assessed values have skyrocketed), but the value of personal property—both exempt and still taxable—has also increased, albeit not in line with the spike in real property values. At current rates, and adjusting for subsequent increases in personal property, the initial $100,000 exemption forgoes about $12.0 million in revenue, while the additional $150,000 exempted in 2022 (bringing the total to $250,000) cost another $8.1 million. Idaho has taken all but the largest payers off the rolls at a cost of about $20 million per year, representing about 12.2 percent of personal property tax—and 1.1 percent of all property tax—collections.

Indiana

Indiana exempts the first $80,000 of personal property from taxation, a policy that exempts over 70 percent of all businesses from personal property tax liability at a cost of 4 percent of personal property tax collections and less than 0.5 percent of all property tax revenues. The exemption was implemented in three stages: first, at $20,000 beginning in 2016,[17] second, at $40,000 under legislation enacted in 2019,[18] and, third, at $80,000 under 2021 legislation. Fiscal estimates were prepared for each proposal separately,[19] but the state has never published an updated cumulative estimate. A Tax Foundation analysis finds that these policies, in aggregate, have eliminated 225,000 businesses (of 320,000) from the tax rolls at a cost of $39.6 million. Personal property taxes generate about $1 billion per year in Indiana, making $39.6 million a trivial amount to exclude over 70 percent of all filers.[20]

In Indiana, property tax millages are calculated based on certified budgets, subject to revenue caps. This means that when some property is exempted, rates can increase—up to certain limits—on remaining taxable property. Consequently, some (but not all) of the decrease in personal property tax revenue was offset by a minuscule increase in taxes on other property, including personal property still on the rolls. For the purposes of our estimates, however, we report the larger value—the amount of revenue forgone from the exempt property, neglecting any offsets that defray those losses.

Exempting 225,500 businesses from the tax came at a revenue loss of less than $176 per business. The first $20,000 in exemptions provided the greatest bang for the buck, at about $105 per exempted business. Notably, this is at the higher end of the range, as Indiana has an unusually high reliance on tangible personal property taxes, which comprise 15 percent of its property tax base, almost three times the national average.

Utah

In Utah, personal property roughly tracks national averages at 4.7 percent of assessed value and 5.5 percent of tax revenue. When lawmakers recently raised the exemption by $10,000 (from $15,000 to $25,000—inflationInflation is when the general price of goods and services increases across the economy, reducing the purchasing power of a currency and the value of certain assets. The same paycheck covers less goods, services, and bills. It is sometimes referred to as a “hidden tax,” as it leaves taxpayers less well-off due to higher costs and “bracket creep,” while increasing the government’s spending power.

adjusted, so $27,000 in 2023), the forgone revenue only totaled $2 million statewide.[21] This represents 0.8 percent of personal property tax collections and 0.04 percent of overall property tax collections, while removing an estimated 36,000 businesses from the tax rolls. An earlier exemption increase, from $3,500 to $10,000, cost $1.9 million while taking 28,300 taxpayers off the rolls,[22] and getting to the initial $3,500 exemption only cost an estimated $136,800.[23]

Design Considerations

Given the minimal costs of exempting TPP, some states have simply adopted the exemption without offsets, confident in localities’ ability to absorb an extremely minor loss of revenue—particularly against the backdrop of soaring property tax collections overall.[24] Often, states have provided revenue offsets to affected localities.

Crucially, businesses below the threshold must be freed from all filing requirements, and local government reimbursements must rely on estimates, not informational reporting. If business owners are required to catalog all assets and file a zero-dollar or informational return reporting the amount they would have owed absent the exemption, they receive none of the intended benefit of forgoing the tax’s high compliance costs. Of course, a business owner whose property might reasonably approach the exemption threshold will still need to run the numbers, but for many small businesses, whether their potentially taxable personal property is above or below a threshold like $100,000 will be immediately obvious.[25]

Most states do not require businesses to itemize personal property if their totals are under the exemption threshold. In some states, like Michigan and Utah, an application or declaration of exemption must be filed, either one time or annually, in lieu of a statement of personal property owned. In others, like Colorado and Indiana, it is not necessary to file anything at all. Somewhat more onerously, Florida requires businesses to file a complete statement of property their first year, but if the total is less than $25,000, then this filing is treated as an application for an exemption from filing in any future year that their personal property does not exceed the threshold. Conversely, Georgia and the District of Columbia require businesses to submit declaration schedules itemizing all potentially taxable personal property even if they are below the threshold, negating the compliance cost benefits of the exemption.

In the absence of informational returns, state officials cannot know exactly how much a locality has forgone due to the exemption. The most straightforward approach, taken by states like Colorado, is to simply inflation-adjust the amount collected on property below that threshold on the last year in which it was taxed. Alternatively, state officials might settle on some reasonable ratio of actual personal property tax collections above the threshold. For instance, if officials concluded that an exemption would reduce personal property tax collections by about 4 percent, then they could provide an ongoing transfer to local governments worth 4.167 percent of what they collect on the personal property still in the tax base.

To preserve the value of the exemptions, lawmakers should also index them for inflation, ensuring that smaller businesses are not drawn back into tax compliance over time. Arizona, Colorado, and Utah currently incorporate automatic inflation adjustments.

Conclusion

Exempting the personal property of small businesses is a highly economical way of reducing taxpayer compliance burdens. The time and resources spent itemizing office chairs and adding up the cost of paper towels is a deadweight loss that hurts businesses without helping local governments, and the revenue generated from this exercise is too trivial to justify its imposition on businesses with minimal tax liability. Ideally, states should seek to eliminate this economically harmful tax altogether, but if they cannot immediately tackle the anti-investment tax itself, at least they can wipe out the inefficiency of small business compliance burdens.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

[1] Kentucky, which has a $1,000 threshold, is not included in this count, as the threshold is so low as to be almost meaningless for businesses of any size, including most sole proprietorships. The state’s threshold is, however, included in the tables below.

[2] Unfortunately, businesses in Washington, D.C., do not obtain the benefit of saving on compliance costs, because they are still required to submit a tax return even if no tax payment is owed, suggesting an obvious avenue for reform.

[3] Maryland Department of Assessments & Taxation, “Instructions for 2023 Form 1, Annual Report & Business Personal Property Tax Return,” 2023, https://dat.maryland.gov/SDAT%20Forms/PPR_Forms/Form1_Instructions_2023.pdf.

[4] Office of the Chief Financial Officer, “FP-31 District of Columbia Personal Property Tax Instructions,” Government of the District of Columbia, Office of Tax and Revenue, 2022, https://mytax.dc.gov/WebFiles/Documents/2022%20FP-31%20Instructions.pdf.

[5] Monroe County Property Appraiser Office, “Tangible Personal Property,” https://mcpafl.org/tangible-personal-property/. Note that, despite this answer, Florida businesses do not need to file in subsequent years if their prior filing showed less than $25,000 in personal property and they have not since exceeded that threshold.

[6] Garrett Watson, “States Should Continue to Reform Taxes on Tangible Personal Property,” Tax Foundation, Aug. 6, 2019, https://taxfoundation.org/research/all/federal/tangible-personal-property-tax/.

[7] Tax Foundation calculations using data from the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy and the U.S. Census Bureau.

[8] For a general review, see John L. Mikesell, “Patterns of Exclusion of Personal Property from American Property Tax Systems,” Public Finance Quarterly 20:4 (October 1992): 528-542.

[9] Peter F. Palmer, “The Abolition of the Personal Property Tax,” The Bulletin of the National Tax Association 26:6 (March 1941): 179.

[10] See, e.g., Sian Mughan and Geoffrey Propheter, “Estimating the Manufacturing Employment Impact of Eliminating the Tangible Personal Property Tax: Evidence from Ohio,” Economic Development Quarterly 31:4 (Sep. 26, 2017).

[11] Thomas Hady, “The Incidence of the Personal Property Tax,” National Tax Journal, 15:4 (December 1962): 372-373.

[12] Colorado Legislative Council Staff, HB 21-1312 Final Fiscal Note, Aug. 24, 2021, https://leg.colorado.gov/sites/default/files/documents/2021A/bills/fn/2021a_hb1312_f1.pdf.

[13] Natalie Mullis, “Memorandum: Business Personal Property Tax,” Colorado Legislative Council Staff, Sep. 10, 2014, https://leg.colorado.gov/sites/default/files/business_personal_property_tax_2014_ip_memo.pdf.

[14] Gary Houde, “2017 Analysis of Potential Full Exemption of Personal Property – Basis and Conditions of Analysis,” Feb. 22, 2018, https://tax.idaho.gov/wp-content/uploads/reports/EPB00733/EPB00733_04-09-2018.pdf.

[15] Idaho Legislature, “Statement of Purpose/Fiscal Note, RS28965 / H0389,” May 3, 2021, https://legislature.idaho.gov/wp-content/uploads/sessioninfo/2021/legislation/H0389SOP.pdf.

[16] Boise State Public Radio, “The Ultimate Guide to Idaho’s Personal Property Tax,” https://www.boisestatepublicradio.org/the-ultimate-guide-to-idahos-personal-property-tax.

[17] Indiana S.B. 1 (2014).

[18] Indiana S.B. 233 (2019).

[19] Legislative Services Agency, Fiscal Impact Statement LS 7115, Indiana Office of Fiscal and Management Analysis, Mar. 19, 2014, https://iga.in.gov/pdf-documents/118/2014/senate/bills/SB0001/fiscal-notes/SB0001.06.ENRS.FN001.pdf; Id., Fiscal Impact Statement LS 6548, Apr. 24, 2019, https://iga.in.gov/pdf-documents/121/2019/senate/bills/SB0233/fiscal-notes/SB0233.06.ENRH.FN001.pdf.

[20] This estimate is likely too low, as the total number of entities—320,000—includes nonprofits and local governments that could not be excluded by Tax Foundation analysis. A denominator that only included for-profit businesses—since they alone pay TPP taxes—would yield a figure substantially higher than 70 percent.

[21] Utah Office of the Legislative Fiscal Analyst, Fiscal Note for S.B. 18 5th Sub., Feb. 27, 2021, https://le.utah.gov/lfa/fnotes/2021/SB0018S05.fn.pdf.

[22] Id., Fiscal Note for S.B. 235, Jan. 11, 2013, https://le.utah.gov/lfa/fnotes/2013/sb0035.fn.pdf.

[23] Id., Fiscal note for H.B. 338 S02, Feb. 6, 2006, https://le.utah.gov/lfa/fnotes/2006/HB0338S02.fn.pdf.

[24] The trivial impact of a TPP de minimis exemption will continue; soaring property tax collections may not, as in time, the dramatic rise in the value of residential real estate will be at least partially offset—especially in major cities—by the softness of the commercial real estate market.

[25] Manufacturers and agricultural operations of almost any size are likely to exceed most exemption thresholds, but most small businesses have relatively few capital investments.

Share