On 12 September, the European Commission released a proposal called “Business in Europe: Framework for Income TaxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities.

ation” (BEFIT) and two associated proposals on transfer pricing and a Head of Office tax system.

BEFIT replaces the Commission’s previous proposals aimed at creating a common corporate tax baseThe tax base is the total amount of income, property, assets, consumption, transactions, or other economic activity subject to taxation by a tax authority. A narrow tax base is non-neutral and inefficient. A broad tax base reduces tax administration costs and allows more revenue to be raised at lower rates.

called CCTB (common corporate tax base) and CCCTB (common consolidated corporate tax base). While the new proposal intends to reduce cross-border frictions for companies operating in multiple Member States, BEFIT relies on financial accounting rules (rather than traditional tax rules) and may end up adding another layer of complexity for business.

BEFIT’s Scope

The BEFIT proposal is designed to build on the OECD’s global tax deal. It includes mandatory obligations for certain companies and voluntary participation for others.

The mandatory scope of the proposal includes multinational companies with global consolidated revenues above EUR 750 million—the same thresholds in Pillar Two. Additional criteria apply for enterprises with an EU ownership share below the 75 percent threshold. Relevant companies—called BEFIT groups—would have to file a single preliminary tax return based on a fictitious common tax base for all their EU-based subsidiaries (BEFIT members).

The preliminary tax returns would then be used to assess compliance risks with transfer pricing rules and allocate shares of the common corporate tax base to EU Member States to which they apply their own national corporate income taxA corporate income tax (CIT) is levied by federal and state governments on business profits. Many companies are not subject to the CIT because they are taxed as pass-through businesses, with income reportable under the individual income tax.

systems. According to the current proposal, Member States would need to implement the new rules by 1 January 2028, with application to BEFIT groups starting 1 July 2028.

Calculating the Base and Allocation Rules

The proposed BEFIT framework moves away from a traditional corporate tax base to one that relies on financial accounting. While this trend is not new—it has been used in Pillars One and Two, as well as the United States’ corporate alternative minimum tax (CAMT)—it can be challenging, complex, and inaccurate. Just because you have a measure of “income” does not mean that it will make a good tax base. A common definition does not necessarily improve upon the approaches at the Member State level.

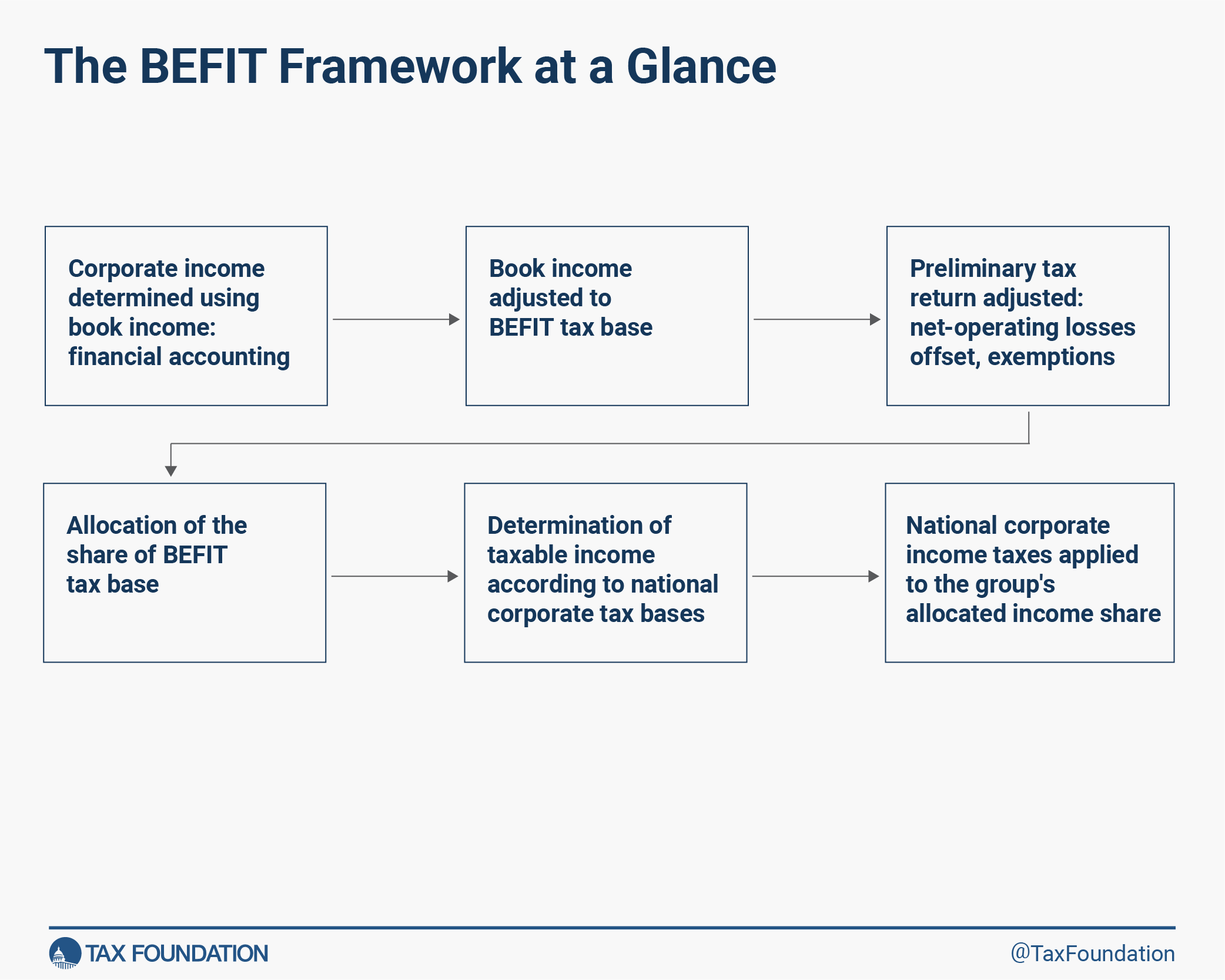

Corporate income is determined using the book incomeBook income is the amount of income corporations publicly report on their financial statements to shareholders. This measure is useful for assessing the financial health of a business but often does not reflect economic reality and can result in a firm appearing profitable while paying little or no income tax.

of the parent entity and adjusting the resulting financial statements according to the BEFIT tax base rules.

The financial accounts statements must follow European Union law, using either the national generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) of one of the Member States or the international financing reporting standards (IFRS). Financial statements produced under these standards reflect book income, a measure used by companies to report their income and expenses to shareholders and creditors to indicate their financial health—a purpose distinct from determining companies’ tax liability.

Offsetting Net Operating Losses and Exempting Certain WithholdingWithholding is the income an employer takes out of an employee’s paycheck and remits to the federal, state, and/or local government. It is calculated based on the amount of income earned, the taxpayer’s filing status, the number of allowances claimed, and any additional amount of the employee requests.

Taxes

Book income is then adjusted in accordance with the rules governing the BEFIT tax base for depreciationDepreciation is a measurement of the “useful life” of a business asset, such as machinery or a factory, to determine the multiyear period over which the cost of that asset can be deducted from taxable income. Instead of allowing businesses to deduct the cost of investments immediately (i.e., full expensing), depreciation requires deductions to be taken over time, reducing their value and discouraging investment.

, inventory treatment, loss carryover provisions, and other changes to arrive at the corporate income measure for the preliminary BEFIT tax return (notably, not always aligned with Pillar Two). For the preliminary tax return, BEFIT groups can offset net operating losses between their members in the same year and are also exempted from withholding taxes on transactions between group members. The latter step seems to be one where substantive cross-border frictions are eliminated, smoothing their business operations across Europe.

But the framework doesn’t stop there. BEFIT groups’ taxable incomeTaxable income is the amount of income subject to tax, after deductions and exemptions. For both individuals and corporations, taxable income differs from—and is less than—gross income.

is then allocated to the Member States using the average share of the BEFIT tax base originating in their jurisdiction over the past three fiscal years. For jurisdictions using distributed profit tax systems, like Estonia and Latvia, an adapted formula is used to allocate national shares taking into account that in these systems; corporate profits are only taxed upon distribution to shareholders.

After the allocation of individual Member States’ shares of the BEFIT tax base, national corporate income taxes are applied to the group’s allocated income share to each jurisdiction. The rules governing the national corporate income tax will usually differ from those of the BEFIT tax base. Therefore, it seems that group members will still have to separately determine their taxable income according to different national rules for all relevant jurisdictions.

One-Stop-Shop or One-More-Stop?

While the proposal speaks of a “one-stop-shop” for EU tax returns, the reality may look more like “one-more-stop.” Instead of filing their national tax returns under a single set of rules, a BEFIT group may have to file one preliminary tax return to calculate the BEFIT tax base allocated to Member States, in addition to all their national tax returns determining their final tax liability. This exerts pressure on Member States to align their national tax laws with the BEFIT tax base to avoid duplicative compliance costs. This means that the chart above only shows the BEFIT tax base for companies, not including what they would have to do in addition to filing their national tax returns.

This introduces an additional layer of complexity for companies. Beyond national corporate taxation and compliance with the 15 percent minimum tax established by Pillar Two, companies will also have to worry about the new BEFIT tax base. Below is a limited summary comparing the GloBE and BEFIT tax bases.

Transfer Pricing Benchmark

The preliminary tax returns filed for BEFIT groups enter a screening process for transfer pricing compliance risk in “low-risk” manufacturing and distribution activities, which are not connected to holding of intellectual property rights.

The proposal introduces a “traffic light” system that evaluates corporate profits from BEFIT tax returns against a profit benchmark—representative for independent entities in these sectors operating in the EU—and classifies the transactions of a BEFIT group within a low-, medium-, or high-risk zone.

If a group’s corporate profits lie considerably below the benchmark, indicating profit shiftingProfit shifting is when multinational companies reduce their tax burden by moving the location of their profits from high-tax countries to low-tax jurisdictions and tax havens.

, the “traffic light” system would flag the company for the “high-risk” category, signalling to national auditA tax audit is when the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) conducts a formal investigation of financial information to verify an individual or corporation has accurately reported and paid their taxes. Selection can be at random, or due to unusual deductions or income reported on a tax return.

ing authorities to take a closer look. Facilitating stronger compliance with transfer pricing policies while dropping withholding taxes on intra-group transactions appears to be a key motivation of the BEFIT proposal.

Since the profit measure under BEFIT differs from companies’ taxable income, an apples-to-apples comparison would require also calculating the equivalent profit measure of independent entities according to BEFIT rules to determine the profit benchmark.

Questions for the European Commission

BEFIT does not appear to meaningfully reduce the complexity of corporate taxation in Europe. While the proposal would eliminate some cross-border frictions within the European Union, it would still create an additional layer of complexity for businesses operating under the framework because it has a different tax base than Pillar Two. Instead of filing their national tax returns under a single set of rules, a BEFIT group may have to file one preliminary tax return for the fictitious BEFIT tax base, in addition to all their legally binding national tax returns. Furthermore, the BEFIT income calculation relies on financial accounting rules, which are distinct from legally binding taxable income.

As currently written, there are fundamental questions the European Commission should answer before being considered by the Council:

- What happens when there is a difference between corporate tax owed under Member State rules and BEFIT rules?

- Are the capital allowanceA capital allowance is the amount of capital investment costs, or money directed towards a company’s long-term growth, a business can deduct each year from its revenue via depreciation. These are also sometimes referred to as depreciation allowances.

s and loss provisions outlined in the proposal more competitive than the status quo? - What will the impact of BEFIT be on the European Union’s Own Resources?

It will be difficult for experts to seriously consider the costs and benefits of the BEFIT proposal without answering these questions. As the current mandate ends next spring, it is imperative that the Commission respond to provide these details in a timely manner.

Note: This post is part of an upcoming BEFIT series that will seek to answer some of these questions, provide a deeper analysis of the proposal, and give some European context.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

Share